Blue Carbon

Metabolism and its controls

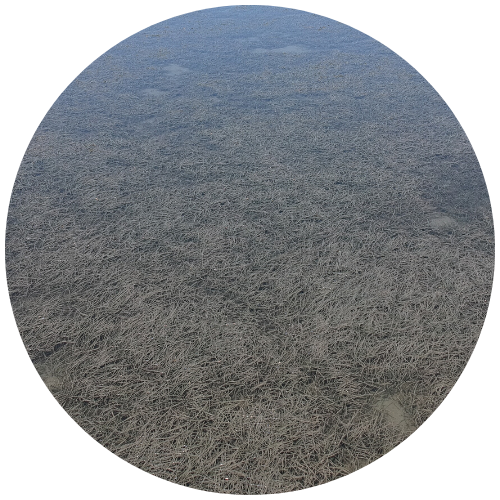

Seagrass meadows are metabolic hot spots in coastal waters that capture and cycle large amounts of carbon. Quantifying seagrass metabolism and understanding its controls is important for motivating and optimizing efforts for restoration and conservation.

Key Findings

Seagrass meadows strongly enhance ecosystem metabolism

• Aquatic eddy covariance is the preferred method to quantify metabolism because measurements are made under in situ conditions without disturbing flow, light, and nutrient exchange; it has a high temporal resolution; and it integrates over a large area (10 -100 m2) (Berg et al. 2003, 2007, 2017, Rheuban & Berg 2013)

• Rates of primary production and respiration in seagrass meadows are 10-25x higher than adjacent bare sediments (Hume et al. 2011, Rheuban et al. 2014a,b)

Drivers of metabolism are complex and vary on different time scales

• Beyond light, on a short time scale (minutes to hours) in situ metabolism is driven by current velocity and wave action (Hume et al. 2011, Rheuban et al. 2014a, Berg et al. 2017)

• On longer time scales (days to years), metabolism varies with temperature and seagrass density (Rheuban et al. 2014b, Berg et al. 2017, Berger et al. 2020)

• Integrated long-term aquatic eddy covariance measurements (11 years) suggest that seagrass meadow production and respiration are balanced, and that carbon burial matches net external inputs to the meadow (Berger et al. 2020)

Seagrass meadows can switch from being a sink to a source of carbon

• Seagrass meadows can shift from being a sink to a source of carbon between months, seasons, and years depending on local environmental conditions (Berg et al. 2019, Berger et al. 2020)

• High-temperature disturbance turned the seagrass meadow from a carbon sink to a source; during recovery the meadow again became a carbon sink (Berger et al. 2020)

• In situ metabolic measurements show no stimulation of photosynthesis at high CO2 and low O2 concentrations, questioning if seagrass will be ‘winners’ in future oceans (Berg et al. 2019)

Storage and offset credits

Seagrass habitats provide important ecosystem services, including supporting diverse faunal communities. Spatial processes, such as dispersal and patchy disturbances, play a role in mediating diversity. We study how the state change from bare sediment to seagrass meadows structures biodiversity and interactions at population and community levels. We also point to work done by our colleagues at the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences on faunal communities.

Key Findings

Restoration reinstates blue carbon stores

• Rates of carbon storage in sediments of seagrass meadows restored by seeding is equivalent to natural meadows after a decade (Greiner et al. 2013)

• Under half of the carbon buried in meadow sediments derives from seagrass; the remainder is either advected into the meadow from adjacent ecosystems or produced in situ (Greiner et al. 2016; Oreska et al. 2017a)

• Sources of buried carbon are: 40% seagrass, 10% marsh, and 50% benthic microalgae; benthic microalgal carbon is produced in situ, not advected into the meadow as previously believed (Greiner et al. 2016; Oreska et al. 2017a)

• Sediment carbon stock are spatially variable and drivers are different on the plot and meadow scales. On the plot scale (m2), meadow age and shoot density determine sediment carbon stocks; at the meadow scale, proximity to the meadow edge is the most important factor (Oreska et al. 2017b)

• Integrated long-term aquatic eddy covariance measurements (11 years) suggest that seagrass meadow production and respiration are balanced, and that carbon burial matches net external inputs to the meadow (Berger et al. 2020)

• Seagrass blue carbon is vulnerable to marine heatwaves. Entire carbon stocks built up in sediments over decades can be lost if meadows die back, as well as carbon sequestration capacity in plant biomass. In some regions, rapid seagrass recovery can prevent large-scale loss. (Berger et al. 2020, Aoki et al. in review)